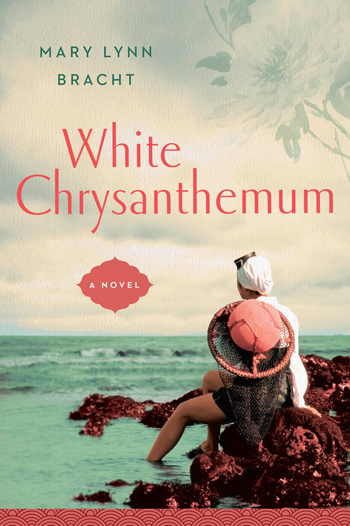

‘White Chrysanthemum’ Is Masterful Look at Comfort Women

The lives of two sisters diverge as each struggles with the realities of war.

You will cry reading Mary Lynn Bracht’s White Chrysanthemum. Multiple times. It’ll hit you in waves. Sometimes only a single tear – others, a small river. You will become invested in these characters such that every travesty perpetrated against them is reflected in yourself. You will feel, at times, torn apart. Bracht’s disturbing piece of historical fiction beautifully weaves together two sisters’ wartime tragedies, creating an all at once engaging – and sometimes fantastical – portrayal of World War II “comfort women.”

Hana and younger sister Emi are haenyeo, a special caste of diving women who harvest from the sea and live outside the bounds of traditional Korean patriarchy. Their special status allows them the freedom to gather and profit from their hard work. Each mother passes on her tradition to the next generation of girls, instilling in them a sense of pride and independence that makes them strong and resilient. But the summer of 1943 brings with it danger worse than drowning: Japanese soldiers.

While her mother is hunting abalone under the waves, Hana spies a soldier approaching Emi on the shore. Too young to dive with her mother and sister, Emi is left to watch the buckets filled with the day’s catch and keep them safe from hungry seabirds. But Emi is only 9, and Hana, seeing the soldier drawing ever closer, plunges into action.

It’s here that Bracht’s story diverges into the events of Hana, captured by Japanese soldiers and forced into a world of sexual slavery, and Emi, the girl saved by her sister’s sacrifice. Hana’s story takes places chronologically from that time on the beach, as she’s taken by boat and train to several locations before more dramatic turns of event force the story in and out of believability but not humanity. Hana’s main nemesis and unrelenting pursuer, Corporal Morimoto, has a Terminator-like steadfastness that tends to overshadow any other characters. He is the main enemy and the embodiment of all others. But where Hana is hounded by Morimoto, Emi is haunted by Hana and the cruelty of war.

We meet Emi every other chapter in 2011. She is an old woman with grown children trying to overcome the loss of her sister, while coping with survivor’s guilt for having outlived most of her friends and family during the end of World War II and into the Korean War. Here Bracht masterfully pulls these two separate but equal stories into each other.

Like knitting, each moment we get from Hana is coupled with an equally enlightening moment from Emi. Without spoiling things, Emi sets off to Seoul to both see her children and attend the 1,000th Wednesday Demonstration in front of the Japanese Embassy, a ritual taking place each week protesting Japan’s seeming denial and lack of culpability for its use of sexual slaves. Her story sheds a light on the aftermath of war and how governments and people work to move on after devastation, or else, cover it up.

Hana’s story, for the most part, is laid bare for all to see. She has nothing to hide, and we see her torment, determination and fight throughout her chapters in the book. Emi, on the other hand, is shrouded in mystery. We gather bits as her story reaches its often heart-wrenching conclusion. We see Emi in the current era and witness her details of life after Hana’s abduction through bits of flashback to her children.

It’s here that Bracht ultimately shines brightest. Her depictions of maternal silence to save her children from heartache are poignantly painted against the backdrop of their reckoning with their own lives. Near the end of the book, Emi says of her daughter, “You followed your heart. That is all I ever wished for both of my children. I’m proud of you … of your choices for your own lives. I’m happy that they were yours to make. Nothing could give me more satisfaction as your mother. You have what I never dreamed of.”

Options and choice play leading roles in both Hana and Emi’s lives throughout the book. To stay or go. To confront or turn away. To speak up or remain silent. And ultimately the lack of choice altogether. Each of these young women takes different turns as a result of war, but each is bound by the sea and a sense of pride in being haenyeo. It’s this that lets each of them survive.

Bracht’s writing, while sometimes stilted, is more often brisk, coaxing you to read the entire book in one sitting. First learning of comfort women from a trip back to her mother’s village in South Korea, Bracht poured into the stories behind those affected by sexual servitude during the war, and her research shows in the book’s vibrant depictions of both wonderous landscapes and extreme cruelty. White Chrysanthemum won’t be for everyone, but it should be. Despite the more fantastical turns near the end of Hana’s journey, Bracht’s story manages to educate and entertain in equal measure without reading as a sermon. A triumph of humanity, White Chrysanthemum will seize you, keeping you held long after you’ve finished the final page.

White Chrysanthemum, Mary Lynn Bracht’s first novel, is available January 30 nationwide. Dumpling was provided a copy for review from Penguin Random House.

Lede photo by amanderson2 of Flickr of haenyeo women diving off the coast of Jeju Island in South Korea. Other photos provided by Penguin Random House. Bracht’s portrait by Tim Hall.

Tags: book review, comfort women, haenyeo, Mary Lynn Bracht, White Chrysanthemum